Portland's Facial-Recognition Ban Sees its First Lawsuit; Baltimore's Ban Expires

In a local-biometrics-regulation update, Portland’s ordinance sees its first enforcement suit, while Baltimore’s ordinance expires under its own sunset provision.

(a) Portland

Almost two years ago, Portland, Oregon, enacted a first-of-its-kind, city-level prohibition on the use of facial-recognition technology by private entities in places of public accommodation. Our previous in-depth discussion of that law can be found here. For present purposes, recall that Portland’s ban:

Applies broadly to use of facial-recognition technology by private entities (essentially, any non-government actor) at “any place or service offering to the public accommodations, advantages, facilities, or privileges whether in the nature of goods, services, lodgings, amusements, transportation or otherwise” within the City of Portland, except for private residences, bona fide clubs, or other non-public institutions.

Has very limited exceptions where use is necessary to comply with law, for verification purposes to access personal or employer-issued electronic devices, and “in automatic face detection services in social media applications.”

Includes a private right of action and a drastic penalty provision, under which those injured by violation of the ordinance may recover the greater of actual damages or $1,000 per day for each day of a violation, plus attorneys’ fees.

Against that background, (what we understand to be) the first lawsuit brought under the ordinance was filed against Idaho-based convenience store chain Jacksons Food Stores in December. (Originally filed in Multnomah County, the complaint was quickly transferred to Oregon federal court and can be found here.)

According to the complaint, Jacksons operates 33 stores within the bounds of Portland, three of which deploy a security-camera system that utilizes facial-recognition technology. Per the complaint, customers attempting to enter these Jacksons stores are made to look into a security camera, which scans their facial features and compares the result to a repository of facial-mapping data for blacklisted persons.

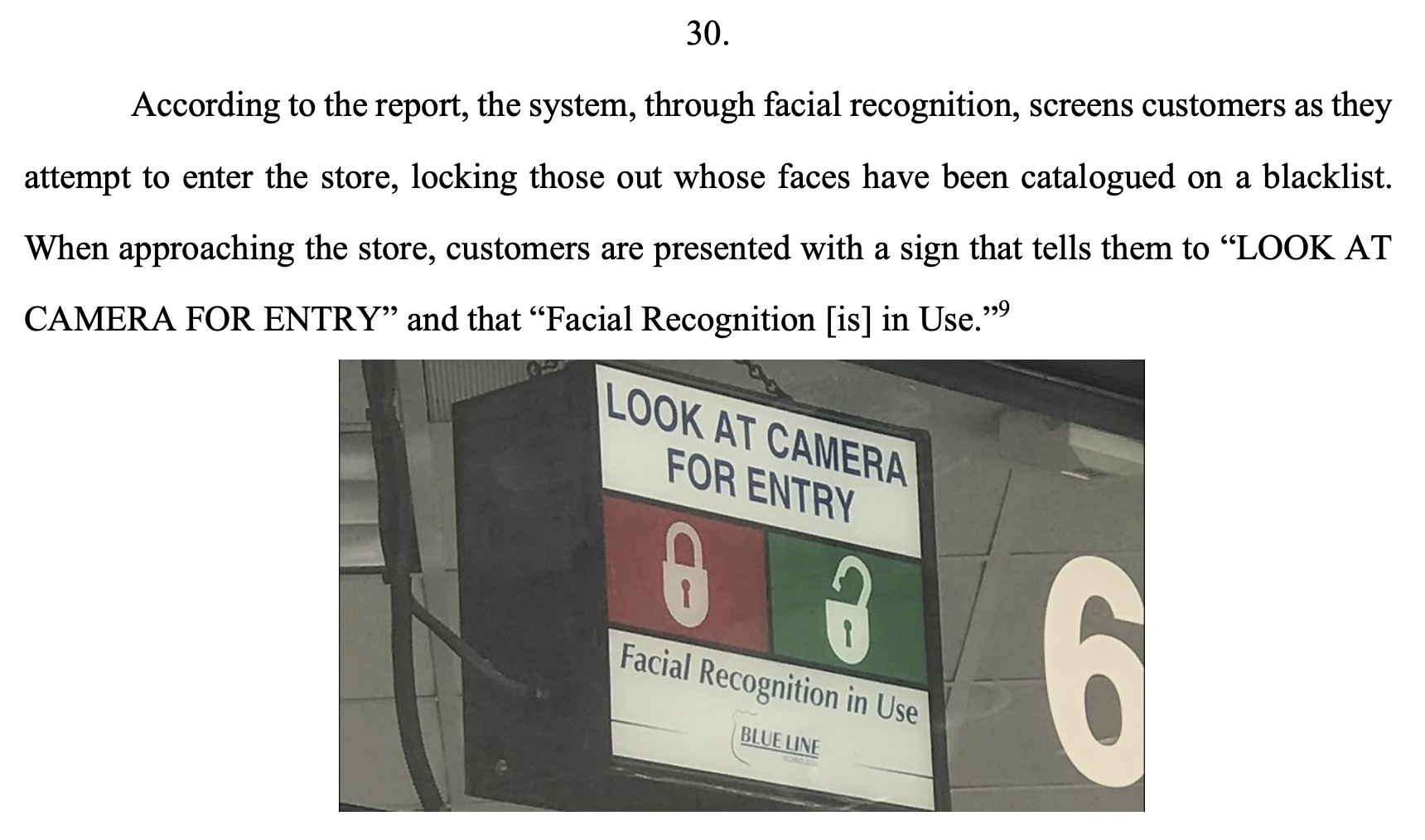

Those who have been added to that blacklist (presumptively, based on prior shoplifting or other malicious conduct) are denied entry to the store. Those who pass the screening, may enter. The technology is provided by Jacksons’ vendor Blue Line Technology, which refers to this system as “First Line Facial Recognition.” The deployment of this system at Jacksons’ stores in Portland was reported first by local news station KGW in 2019. The complaint alleges that Jacksons continues to utilize this technology.

Plaintiffs allege they were subject to this use of facial-recognition technology in violation of Portland’s ordinance while visiting a Jacksons store in Portland after January 1, 2021 (when the ordinance took effect), and are looking to represent a class of all similarly situated parties. Plaintiffs seek the greater of actual damages or statutory damages of $1,000 per day for each day of the violation [query which measure will prove greater], as well as attorneys’ fees and costs. The complaint seeks damages of not less than $10,000,000.

Should this case make it to a ruling on a merits, one interesting thing to watch will be how the “per day” measure of damages is applied. The complaint’s calculation of potential damages seems to suggest - and this author thinks a reasonable read of the ordinance text would support - that statutory damages are measured for each individual that comprises the proposed class. However, is every member of the class entitled to a per-day recovery of damages for the entire period between when the ordinance took place and when the offending security system is/was discontinued? Or can each individual recover only for those days during which he or she was actually scanned by the security system while visiting a Jacksons store? (Or, as a possible middle ground, only for those days after his or her initial scan?) If class members are not entitled to recover for days of the alleged violation that occurred before that individual class member actually visited a Jacksons Food Store, particularized questions of who is owed what may complicate class certification.

The case is Norby v. Jacksons Food Stores, Inc., No. 3:23-cv-00005 (D. Or. transferred Jan. 3, 2023)

(b) Baltimore

Baltimore, like Portland, adopted a city-level ordinance prohibiting the use of facial-recognition technology. (For a full rundown of the Baltimore law, please see our previous post here.) By its own terms, that ordinance included a sunset period whereby it would terminate December 31, 2022, without further action by the City Council to maintain it. The Council does not appear to have renewed the 2021 ordinance, and, while some Baltimore city council members have expressed a desire to explore new regulation of facial-recognition technologies, the 2021 ordinance has now expired and is no longer effective.

Originally published by InfoLawGroup LLP. If you would like to receive regular emails from us, in which we share updates and our take on current legal news, please subscribe to InfoLawGroup’s Insights HERE.